Remembering Simplified Hanzi

- #public

- subtitle:: How Not to Forget the Meaning and Writing of Chinese Characters zi]] by James Heisig and Timothy W. Richardson.

- Sample https://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/en/files/2013/11/RH-S1-sample.pdf

- Write up/review: [[How I learned 1500 Chinese Characters in a Month - Heisig Method Review]]

- By showing how to break down the complexities of the characters into their basic elements, assigning meanings to those elements, and arranging the characters in a unique and rational order, the method aims to make use of the structural properties of the writing system itself to reduce the burden on memory.

- Chinese frequent characters

- We settle on introducing a total of 3,000 most frequently used characters.

- This number may fall below the 3,500 to 4,500 characters that are generally thought necessary for full pro-ficiency, but it also happens to represent about 99.5% of the characters found in running Chinese texts, as large-scale frequency counts show.

- What is more, students who have learned to write these 3,000 characters will be equipped with the tools for learning to write additional characters as the need arises.

- Next, since the top 1,000 entries in our complete frequency list account for approximately 90% of characters in running texts we decided to include all of them in the first book of both the traditional and simplified sets.

- Frequency lists

- Frequency lists compiled by specialists do indeed exist. Some of them list only traditional characters and others only simplified; some of them are more formal and others less so; some of them are more technical and some less so; and so forth.

- What we wanted, however, was a general-use list of 3,000 characters that would apply to the whole of the Chinese-speaking world. In a strict sense, such a list is not possible.

- We therefore consulted a list of the 969 characters taught in the first four grades of elementary school in the Republic of China.

- We settle on introducing a total of 3,000 most frequently used characters.

- Approach

- Focus on characters first

- If some separation of learning tasks seems reasonable, then why not acquire a sizable vocabulary of Chinese pronunciations and meanings first—as the Chinese children do—and then pick up writing later? After all, oral language is the older, more universal, and more ordinary means of communication. Hence the bias that if anything is to be postponed, it should be the introduction of the writing system. The truth is, written characters bring a high degree of clarity to the multiplicity of meanings carried by homophones in the spoken language.

- We acknowledge that effective reading requires a knowledge of compound words and grammatical patterns; however, we concur with those who stress the value of learning individual characters well in order to solidify “the network of possible morphemes upon which all dual and multi-character words are built.”

- If some separation of learning tasks seems reasonable, then why not acquire a sizable vocabulary of Chinese pronunciations and meanings first—as the Chinese children do—and then pick up writing later? After all, oral language is the older, more universal, and more ordinary means of communication. Hence the bias that if anything is to be postponed, it should be the introduction of the writing system. The truth is, written characters bring a high degree of clarity to the multiplicity of meanings carried by homophones in the spoken language.

- Using mnemonics to learn Chinese

- The dominant bias against the use of mnemonics for learning Chinese characters is that it is inappropriate to overstep the boundaries of current ety-mological knowledge, even more so when these liberties are taken without drawing attention to the fact. To do so is not to communicate the “truth” about the characters.

- Still another apprehension some may have is that mnemonic devices clutter the mind and separate the learner from the matter to be learned. On the contrary, insofar as such devices provide meaning and organization that would not oth-erwise exist, they actually unclutter the mind. Besides, once recall for a particu-lar item has become automatic, the mnemonic initially used to fix that item in memory usually falls away of its own accord.

- These scholarly developments also help address another concern: mnemonics are simply too bizarre or too silly to use. Actually, they can be quite sophisticated and elegant.

- The approach followed in these pages incorporates important elements of all three broad areas into which cognitive learning strategies are thought to fall—organization, elaboration, and rehearsal—and entails a strong reliance on memory techniques or “mnemonics.”

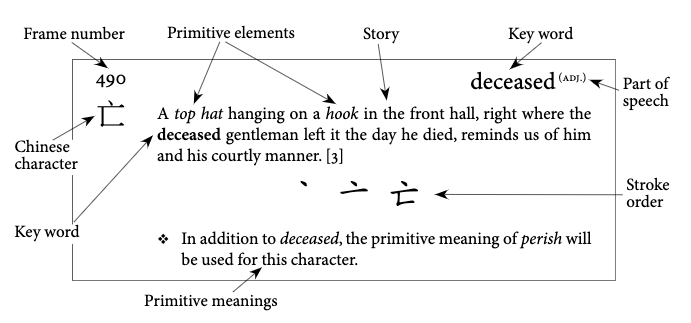

- primitive elements

- All the characters are made up of pieces,

- These are the basic building blocks out of which all characters are constructed.

- Over 200 of these have been singled out as “radicals,” which are used in the organization of character dictionaries, but there are many others.

- Individual characters can also serve as primitive elements in other more complicated characters.

- If one is really determined to learn to write Chinese, and not just memorize a small number of characters to meet course requirements, it makes sense to take full advantage of these component parts by arranging the characters in the order best suited to memory.

- This course begins, therefore, with a handful of uncomplicated primitive elements and combines them to make as many characters as possible.

- More elements are then thrown into the mix, a few at a time, allowing new characters to be learned—and so on, until there are no more left.

- Each primitive element is assigned its own concrete image, after which the images are arranged into a composite picture associated with a definition, a unique “key word,” given for each character.

- The key word is meant to capture a character’s principal meaning, or at least one of its more important meanings.

- It is often concrete and visually suggestive, but it can also be conceptual and abstract.

- It is the key word, or its use in a familiar English phrase, that sets the stage for the composition of the elements into a single “story.”

- The stories are meant to stretch your imagination and get you close enough to the characters to befriend them, let them surprise you, inspire you, enlighten you, resist you, and seduce you; to make you smile or shudder or otherwise react emotionally in such a way as to fix the imagery in memory.

- The whole process employs what we may call imaginative memory, by which we mean the faculty to recall images created purely in the mind, with no actual or remembered visual stimuli behind them. We are used to hills and roads, to the faces of people and the skylines of cities, to flowers, animals, and the phenomena of nature associated with visual memory. And while only a fraction of what we see is readily recalled, we are confident that, given proper attention, anything we choose to remember, we can.

- The stories are meant to stretch your imagination and get you close enough to the characters to befriend them, let them surprise you, inspire you, enlighten you, resist you, and seduce you; to make you smile or shudder or otherwise react emotionally in such a way as to fix the imagery in memory.

- All the characters are made up of pieces,

- Organization

- Since the goal is not simply to remember a certain number of characters, but to learn how to remember them (and others not included in the course), this book has been divided into three parts.

- Stories, provides a full associative story for each character. By directing the student’s attention, at least for the length of time it takes to read the explanation and relate it to the written form of the character, we do most of the work, even as the student acquires a feeling for the method.

- Plots, only skeletal outlines of stories are presented, leaving it to the student to work out the details by drawing on personal memory and fantasy.

- Elements, comprises the major portion of the book, and provides only the key word and the primitive meanings, leaving the remainder of the process to the student.

- Two volumes

- The complete list of 3,000 characters has been divided into two volumes of 1,500 each, which can be studied either sequentially or simultaneously.

- An advantage to studying the two volumes side by side is that all the characters that logically fall together at any given point can be learned at the same time. Details on this simultaneous approach are provided in the Introduction to Book 2.

- The complete list of 3,000 characters has been divided into two volumes of 1,500 each, which can be studied either sequentially or simultaneously.

- Since the goal is not simply to remember a certain number of characters, but to learn how to remember them (and others not included in the course), this book has been divided into three parts.

- Benefits of scale

- using the method laid out in these pages to learn 3,000 characters, rather than 1,000, for instance, results in a decrease in learning cost per character, because an investment in basic mental “machinery” is largely made early on. In other words, time and effort expended at the outset yields much better returns as more characters are learned.

- Focus on characters first

- Reviewing

- It should not be assumed that, because the first characters are so elementary, they can be skipped over hastily.

- The method presented here needs to be learned step by step, lest you find yourself forced later to retreat to the first stages and start over.

- Some 20 or 25 characters per day would not be excessive for someone who has only a couple of hours to give to study. If you were to study them full time, there is no reason why all 1,500 characters in Book 1 could not be learned successfully in four to five weeks.

- The characters are best reviewed by

- beginning with the key word,

- progressing to the respective story,

- and then writing the character itself.

- Writing

- Second, the repeated advice given to study the characters with pad and pencil should be taken seriously.

- While simply remembering the characters does not, you will discover, demand that they be written, there is really no better way to improve the aesthetic appearance of your writing and acquire a “natural feel” for the flow of the characters than by writing them.

- The method of this course will spare you the toil of writing the same character over and over in order to learn it, but it will not supply the fluency at writing that comes only with constant practice.

- If pen and paper are inconvenient,

- you can always make do with the palm of the hand, as the Chinese themselves do. It provides a convenient square space for tracing characters with your index finger when riding in a bus or walking down the street.

- Second, the repeated advice given to study the characters with pad and pencil should be taken seriously.

- Once you have been able to perform these steps, reversing the order follows as a matter of course.

- It says: when you review, review only from the key word to the character, not the other way around. The reasons for this, along with further notes on reviewing, will come later. Why is this?

- Take a moment in this very first frame to make sure you understand the difference between key words and primitive meanings.

- The key word represents the actual meaning of the character.

- Primitive meanings

- only used in stories of other characters, not necessarily related to meaning

- added occasionally to make the image of a character more concrete when it functions as a component part of other characters. You will soon see how much these primitive meanings broaden your options for creating memorable stories.

- It should not be assumed that, because the first characters are so elementary, they can be skipped over hastily.

- References

- For more developed arguments making a case for mnemonics, see K. L. Higbee, Your Memory: How it Works and How to Improve it (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1988); see also T. W. Richardson, “Chinese Character Memorization and Literacy: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives on a Sophisticated Version of an Old Strategy,” in Andreas Guder, Jiang Xin, and Wan Yexin, eds., 對外漢字的認知与教學 [The cognition, learning, and teaching of Chinese characters] (Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press, 2007). #memory #mnemonic

- E. B. Hayes, “The Relationship between ‘Word Length’ and Memorability among Non-Native Readers of Chinese Mandarin,” Journal of the Chinese Language Teacher’s Asso-ciation 25/3 (1990), 38

- Original book: Adventures in Kanji-Land (1978)

- T. W. Richardson, James W. Heisig’s System for Remembering Kanji: An Examination of Relevant Theory and Research, and a 1,000-Character Adaptation for Chinese. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, 1998

- Timothy Richardson, a language teacher who had studied some Chinese at the university level, came upon a copy of Remembering the Kanji in the early 1990s. He quickly became interested in the possibility of adapting the work for students of Chinese.

- In subsequent doctoral work at the University of Texas at Austin, he focused on the method for his dissertation and subjected it to an extensive examination in terms of relevant theory and research.

- This required careful consideration not only of the underlying cognitive processes that the method might be expected to involve but also of its reasonableness in terms of prevailing perspectives on vocabulary development and reading.

- His work also entailed the compilation of a new list of 1,000 high-frequency Chinese char-acters and their integration into a skeletal Chinese version of Heisig’s original book.

- Interesting to think about this kind of work (of which I've seen others before) which do the work of systematizing and providing you with ready-made mnemonics, with the work of Andy Matuschak on Quantum Country, providing carefully designed pre-written Spaced Repetition questions. Also interesting that most of this work was done in analogue books - now we have the possibility (perhaps) of collecting usage data to calibrate which stories/questions etc work better (as a whole, or even for individual learners)?

Referred in

A: Chinese

#public Motivation Reading [[How I learned 1500 Chinese Characters in a Month - Heisig Method Review]] , about the book [[Remembering…

How I learned 1500 Chinese Characters in a Month - Heisig Method Review

#public link #instapaper by Pavel Danov #memory How do memories transition from memory palaces to normal memory? Hack to get it into…

If you think this note resonated, be it positive or negative, send me a direct message on Twitter or an email and we can talk.